3 speeches you haven’t heard of that changed the world

Speeches created and delivered as part of a leader’s strategic executive communications often pave the way for change – just like these three historical speeches did.

Chances are you’ve never heard of the speeches below, even though the speakers who delivered them are well-known.

Take a look at what can happen in the world when a speech is crafted with intention to plant the seeds for change.

Could your next speech do the same?

The takeaways shared here are important for every leader delivering strategic executive communications today.

‘Eyes of the Blind’

A speech by Helen Keller, delivered March 27, 1930, at the Committee on the Library, U.S. House of Representatives, Washington, D.C.

All of us know well the early accomplishments of Helen Keller: the little girl who, despite being deaf and blind at 19 months, learned to conquer language and communicate thanks to the efforts of her beloved teacher Annie Sullivan.

In 1904, Keller became the first deaf-blind person in the U.S. to earn a college degree, graduating from Radcliffe College of Harvard University with a bachelor of arts.

As an adult, she delivered more than 400 public speeches, advocating often for disability rights, social justice and education.

Her first speech was in 1913 at a New Jersey elementary school, where she acknowledged that most people are blind to the suffering of others.

“If we had a penetrating vision,” she said, “we would not endure what we see in the world today.”

Beginning in 1924, Keller traveled the world to advocate on behalf of the American Foundation for the Blind. In this role, she spoke up for people with vision loss (even though she knew her own voice as a public speaker was sometimes difficult for audiences to understand).

Six years later, in her first speech before Congress on March 27, 1930, Keller asked the federal government to fund a program to create Braille books for blind adults.

What she said

Her remarks were brief – just 379 words – but memorable.

Here is one excerpt:

“Books are the eyes of the blind. They reveal to us the glories of the light-filled world, they keep us in touch with what people are thinking and doing, they help us to forget our limitations. With our hands plunged into an interesting book, we feel independent and happy.

“Have you ever tried to imagine what it would be like not to see? Close your eyes for a moment. Go to the window keeping your eyes shut. Everything out there is a blank – the street, the sky, the sun itself! You cannot distinguish the houses from the trees, nor tell where one object ends and another begins. All is confusion. You grope your way back to your chair. You sit down helpless. A sense of loneliness creeps over you. You feel shut in by an impenetrable wall.“

She closed with this plea:

“I ask you to show your gratitude to God for your sight by voting for this bill.”

After this speech, what changed in the world?

One year later, the government agreed to begin creating and circulating free Braille books to people with vision loss via the Pratt-Smooth Act, signed into law by President Herbert Hoover.

Today, this program is known as the National Library Service for the Blind and Print Disabled.

Takeaways for strategic executive communications today

- Brevity with impact – Keller made her point in just 379 words. Can you make your message more concise?

- Personal credibility – Keller’s experience as a deaf-blind person made her an authentic, credible source for her message. Can you draw on your own personal experiences to make your audience see you as authentic and credible?

- Empathy, perspective and emotional appeal – Keller asked her audience to imagine life without sight, fostering empathy and emotion. Can you share an experience that fosters empathy and elicits an emotional response?

- Clarity of purpose – Keller’s ask was unmistakable: fund Braille books. Could you be clearer and more direct in your strategic executive communications?

- Call to action – Keller’s closing plea was actionable: “Show your gratitude to God for your sight by voting for this bill.” Do you end your speeches with a definite call to action?

‘Of Man and the Stream of Time’

A speech by Rachel Carson, delivered June 12, 1962, as a commencement address at Scripps College, Claremont, Calif.

By the early 1960s, marine biologist Rachel Carson had gained quite a reputation as a leading science writer and advocate for environmental awareness. Her books, “The Sea Around Us” (1951) and “The Edge of the Sea” (1955), made her a pioneering voice about the interconnectedness of humankind and nature.

Carson’s notoriety as a trusted voice in science communication likely inspired Scripps College to invite her to deliver its 1962 commencement address on June 12.

Carson spoke about “man’s attitude toward nature … a subject of immediate and sometimes terrifying relevance.” She urged the graduating class to face environmental realities and embrace their responsibility to shape a sustainable future.

What she said

Throughout the speech, Carson’s scientific precision and poetic beauty shine forth:

“Man has long talked somewhat arrogantly about the conquest of nature … there is all too little awareness that man is part of nature, and that the price of conquest may well be the destruction of man himself.”

She went on to say:

“It is good that fear and superstition have largely been replaced by knowledge, but we would be on safer ground today if the knowledge had been accompanied by humility instead of arrogance.”

She disparages the notion of a world set up for “man’s use and convenience”:

“We still talk in terms of ‘conquest’ whether it be of the insect world or the mysterious world of space. We still have not become mature enough to see ourselves as a very tiny part of a vast and incredible universe, a universe that is distinguished above all else by a mysterious and wonderful unity that we flout at our peril.”

She sounds the alarm numerous times:

- “Man’s attitude toward nature is today critically important, simply because of his new-found power to destroy it.”

- “We now wage war on other organisms, turning against them all the terrible armaments of modern chemistry, and we assume a right to push a whole species over the brink of extinction.”

- “Wholly new chemicals are emerging from the laboratories, an astounding, bewildering array of them. All of these things are being introduced into our environment at a rapid rate. There simply is no time for living protoplasm to adjust to them.”

She suggests what we should do next:

“Instead of always trying to impose our will on nature, we should sometimes be quiet and listen to what she has to tell us.

“If we did so, I am sure we would gain a new perspective on our own feverish lives.”

She ends with this:

“Your generation must come to terms with the environment. You must face realities instead of taking refuge in ignorance and evasion of truth.

“Yours is a grave and sobering responsibility, but it is also a shining opportunity.

“You go out into a world where mankind is challenged, as it has never been challenged before, to prove its maturity and its mastery not of nature, but of itself.

“Therein lies our hope and our destiny.

“‘In today already walks tomorrow.’“

After this speech, what changed in the world?

Carson’s warnings and calls to action in her commencement address were a prologue to her upcoming series in The New Yorker just four days later. That series exposed the dangers of pesticides – specifically DDT – and their harm on ecosystems and human health.

Three months later, Carson’s series was published as “Silent Spring,” her now infamous book, which positioned her as a moral leader on the urgent need to address critical environmental issues.

“Silent Spring” sparked widespread public debate and concern about chemical pollution and launched the modern environmental movement.

The momentum from Carson’s messages in 1962 eventually led to the creation of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in 1970 and the U.S. ban of DDT for agricultural use in 1972. Her work inspired environmental legislation like the Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act and Endangered Species Act.

Takeaways for strategic executive communications today

- Sound the alarm with authority – Carson highlighted urgent environmental dangers with scientific credibility. Can you use data-driven insights to address pressing issues in your organization or industry?

- Challenge conventional thinking – Carson criticized humanity’s “arrogance” toward nature. Can you be bold and question entrenched thinking to drive innovation and progress?

- Frame responsibility as opportunity – Carson said the graduates had a “shining opportunity” to address environmental crises. Can you inspire your team by presenting challenges as a chance for making a meaningful impact?

- Lead with vision – Carson demonstrated visionary leadership by foreshadowing the environmental movement. Can you anticipate future challenges and position your organization as a bold agent of change?

- Close with hope – Although her message was urgent and full of warnings, Carson ended by affirming humanity’s potential for self-mastery. Can you balance realism with optimism in your strategic executive communications to motivate your audiences to take the next step?

‘Discrimination against Women’

A speech by Patsy Mink, delivered June 24, 1970, to the Special Subcommittee on Education, Committee on Education and Labor, U.S. House of Representatives, Washington, D.C.

In 1964, Patsy Takemoto Mink – a Democrat who’d served not only in the Hawaii Territorial House and Senate but also in the Hawaii State Senate – made history by becoming the first woman of color and the first Asian-American woman elected to the U.S. Congress.

A trailblazing American politician, Mink was an advocate for equality and social justice after experiencing both racism and sexism early in her life. Despite a stellar academic record, she was rejected by medical schools; instead, she pursued law, graduating from the University of Chicago Law School in 1951.

During her first six years in the U.S. Congress, Mink focused on education legislation, anti-Vietnam War issues and civil rights, challenging racial discrimination in education and housing.

In the summer of 1970, fellow congresswoman Edith Green from Oregon began organizing hearings to address sex discrimination in higher education – a topic not yet part of the national conversation – and identified women who could provide testimony.

Green invited Mink to speak on June 24, 1970, to help build the case for legislative action. Mink stepped up, highlighting systemic discrimination against women in higher education and its impact on human potential, along with widespread inequalities, unequal policies and challenges faced by female educators.

Mink urged Congress to address these inequities through laws that would ensure equal opportunities for women in education.

What she said

Mink called discrimination against women in education “one of the most insidious forms of prejudice extant in our nation.”

Then, with tenacity and eloquence, Mink made her case, delivering testimony linking gender equality in education to societal progress.

Here is one excerpt:

“Our nation can no longer afford this system which demoralizes and demeans half the population and deprives them of the means to participate fully in our society as equal citizens. Lacking the contribution which women are capable of making to human betterment, our nation is the loser so long as this discrimination is allowed to continue.”

Toward the end of her testimony, Mink said:

“Congress must act now to eliminate such glaring favoritism in our laws. It is no longer a matter of just equity … Our country is now in a position where it can no longer afford to rely on the anti-deluvian [sic] notion that men should rule the world. We need women; their abilities and talents must be fully utilized.

“Our nation’s future is the most compelling reason for the adoption of these provisions …”

After this speech, what changed in the world?

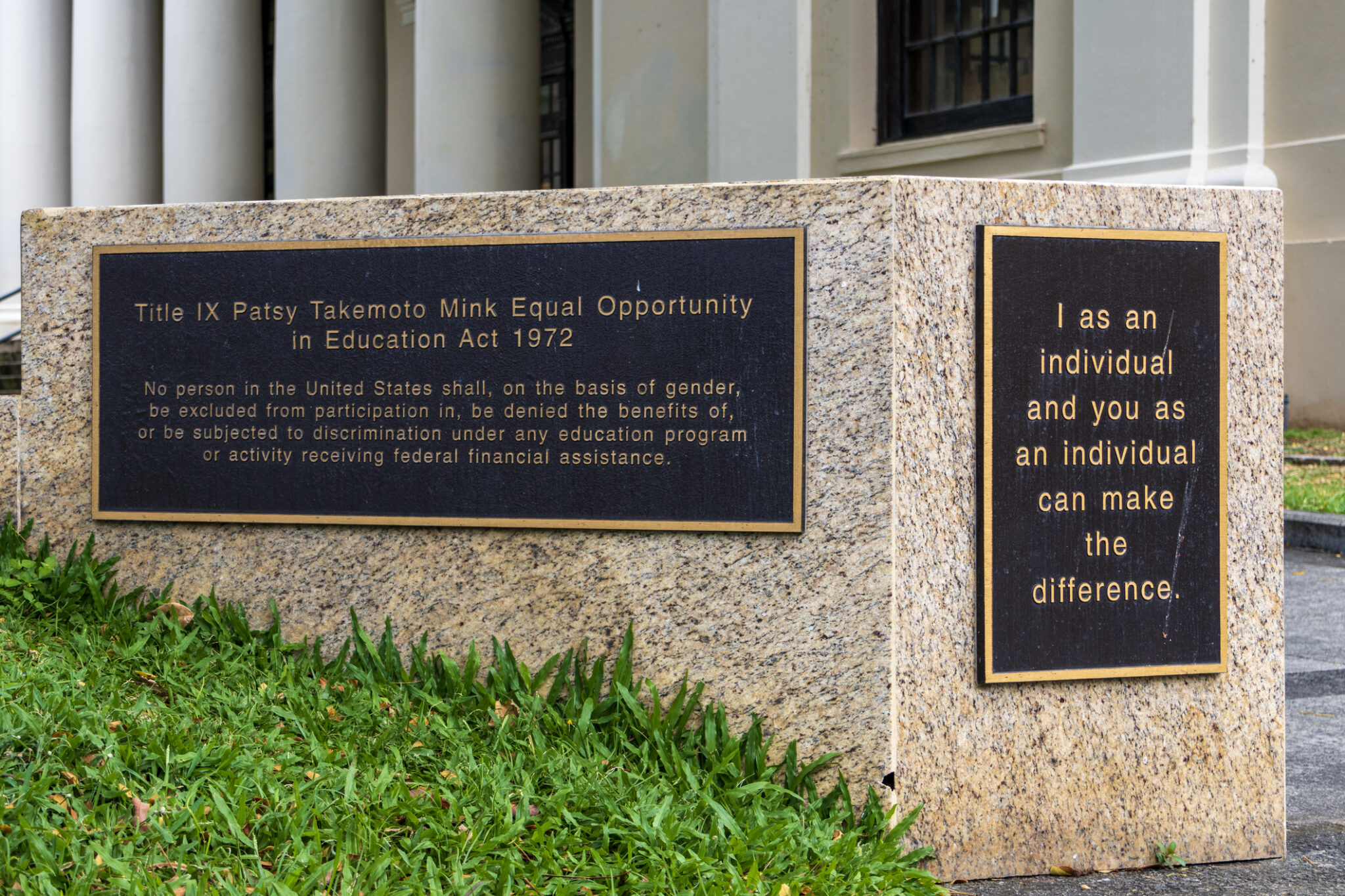

While testimony provided by Mink and others didn’t result in change right away – the 1970 legislation did not pass – it laid the groundwork and set the momentum for a new statute, Title IX of the Education Amendments, based on language Green and Mink drafted as its co-authors.

Title IX, which prohibited sex discrimination in federally funded educational institutions, was signed into law by President Nixon in 1972.

Title IX changed everything for women in education, from hiring to promotion to admissions. It also changed athletics since it provided equitable access to programs, scholarships and coaching positions. Women also received protections against sexual harassment and discrimination based on pregnancy status.

After Mink’s death in 2002, the official name of Title IX was changed to the Patsy T. Mink Equal Opportunity in Education Act.

Takeaways for strategic executive communications today

- Link issues to broader progress – Mink connected gender equality in education to national progress and human betterment. To inspire collective action, can you frame your initiatives as part of a larger mission?

- Use data and logic to help persuade – Mink rooted her testimony in evidence and reasoned arguments. Can you strengthen your strategic executive communications by presenting clear data and logical reasoning to build credibility?

- Speak with moral authority – Mink was authentic because she drew on her personal experiences with racism and sexism. Can you leverage your own experiences to connect with audiences on a deeper level?

- Confront outdated norms – Mink rejected the “antiquated notion that men should rule the world.” Can you question outdated practices to drive a new way ahead?

- Call for immediate action – Mink’s plea was urgent: “Congress must act now.” When addressing a pressing challenge, what bold statement can you make to underscore urgency?

What you can do next

These three historical speeches – two congressional testimonies and a college commencement speech – ultimately changed the world.

Ask yourself:

In my strategic executive communications today, how can I apply some of the 15 takeaways from these three historical speeches to pave the way for change?

Opportunity?

Or progress?

Need help ensuring your speeches and strategic executive communications will resonate?

Contact Teresa Zumwald: a 20-time winner of the Cicero Speechwriting Awards who delivers custom speechwriting services, plus executive speech coaching, executive communications, and speaking and training.